- Topic

- Urban mobility planning

- Country

- Netherlands

- Resource type

- Case study

First published on 29 November 2022.

How do you keep a city accessible while the demand for mobility is growing year on year? How do you ensure a modal split in which sustainable modes predominate? The Dutch city of Utrecht has been successful in promoting the use of sustainable means of transport over recent years, and this case study looks at the city’s mobility policy and plans in its latest SUMP.

Context

Utrecht is a city of 350,000 inhabitants in the centre of The Netherlands. It has been growing in population, employment and GDP year on year for most of the past decade. Further growth is expected: its population is likely to increase to 450,000 by 2040, while employment is expected to grow by an average of more than 4,000 jobs per year to reach 350,000 jobs in 2040, which amounts to an increase of 25% between 2020 and 2040. With this growth comes an increase in mobility. The expectation is that the expansion of the city will result in approximately 35% more trips in 2040 compared to 2015. The key to sustainable urban mobility is how to manage this growth, while keeping the city accessible and its environment and people healthy?

So far, Utrecht has had some remarkable results in promoting sustainable urban mobility. For example, the city is particularly well known for its cycling, but there are other interesting examples. In 2021 Utrecht adopted an updated SUMP and this case study examines some of the achievements delivered by the previous plan and Utrecht’s ambitions for the future.

In action

Over the past five years, urban mobility planning in the city has been guided by the Mobility Plan Utrecht 2025, which was adopted in 2016. Within this plan, the city council intended to take a big step towards linking mobility and spatial planning through densification, in particular through transport hubs, mixed-use land planning, and better integration into physical space. It prioritised walking and cycling, creating safe and attractive public spaces for these modes, while confining motorised traffic, as much as possible, to a dedicated network of a city ring-road and roads that access public transport hubs, thus enabling drivers to access the city using sustainable transport. In addition, the plan included a clear link with the spatial development strategy of the city, focusing on transit-oriented development.

To achieve the ten specific objectives formulated in the Mobility Plan – action plans and area agendas were drawn up, targeting cycling, pedestrians, urban logistics, clean mobility and road safety. Each focused on the horizon of 2015-2020.

The Cycle Action Plan aimed at improving the quality of the main cycling network, including traffic flow at traffic lights, and improving road safety. In addition, it aimed to create more parking spaces for bicycles and more space and safe routes for cyclists around road works. To achieve this, some 129 projects were implemented between 2015-2020. On several key cycling routes, road space was reassigned from motorised traffic to bicycles by turning them into ‘bicycle streets’ or an extended version of “edge lane roads”. In the latter case, road space for all motorised traffic was reduced from two lanes to one in both directions. In addition, speed limits were reduced to 30 km/h. The choice of a mixed-use approach, instead of creating separate cycle paths, was to communicate the priority given to cyclists.

Utrecht’s Pedestrian Action Plan was the first such plan in The Netherlands. Its key aims were to make walking a more appealing mobility option and to create a safer environment for pedestrians. The plan included 13 actions, ranging from the creation of clear routes to improving public spaces and communication campaigns. Since the adoption of the action plan, approximately 45 redevelopment projects have been carried out, or are under preparation, whereby more space has been, or is being, created for pedestrians. In addition, urban planning guidance was established for current and future developments, which should establish a pedestrian-oriented, low-traffic environment.

To create space for pedestrians and cycling, as well as a pleasant and green environment, space for street parking was reduced in line with the city’s Parking Vision. At the same time, in a further effort to manage mobility patterns, parking fees for on-street parking were introduced in a much wider area and new parking spaces in the form of the ‘park-and-ride’ (P+R) locations were created at the city’s edges. These P+R locations were integrated into a developing network of multimodal hubs, which also offer access to shared and public transport options. Many actions to develop and improve public transport and convince people to adopt more sustainable mobility patterns were developed and implemented in close coordination with regional stakeholders.

Neighbouring municipalities have been intensively involved in the development of Utrecht’s Mobility Plan. Together with the local public transport authority and neighbouring municipalities, plans were made for a regional network of hubs and public transport services. Cooperation with some 200 employers in the region, which together had around 70,000 employees, in the programme ‘Goedopweg’ was used to seduce commuters in the region to change their travel behaviour by working from home more often, sharing rides to work, travelling outside rush hours and shifting from the car to the bicycle or public transport. Actions in the urban mobility plan targeting freight were also guided by an overarching regional plan: the regional Quality Network for Freight Transport, which defined preferred routes for freight transport by road, water and rail, and included quality standards. A limited number of these routes provide access for freight transport to the city. These link a network of hubs/transfer points and the main origins and destinations in the city with its ring roads. The connections to the ring road are short and have particular features: special traffic light settings, wider lanes and (for environmentally-friendly freight transport) joint use of bus lanes and charging facilities.

The Action Plan on Clean Mobility primarily focused on the promotion of e-mobility through the development of the charging network, raising awareness, stimulating clean shared-mobility initiatives and investing in zero-emission municipal and public transport vehicles. In addition, a low emission zone came into force in 2015, targeting freight and passenger vehicles.

Results

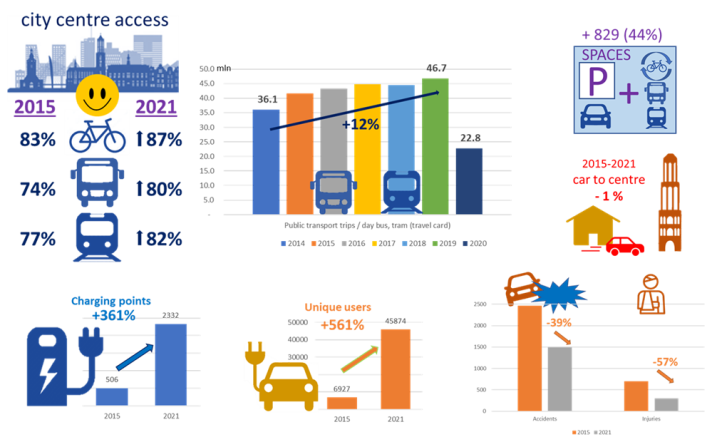

The projects from the cycling action plan greatly contributed towards the creation of a true cycling environment in the city, an environment that has received international praise, with Utrecht being named Best Cycling city in 2020 and 2022 and featuring within the top three of the “Copenhagenize Index” since 2013. The projects also contributed to an increase in bicycle use by an average of 3-5% per year over the 2015-2020 period. Satisfaction with the accessibility of the city centre by sustainable modes increased during the 2015-2020 period to a level where almost nine out of ten inhabitants were either satisfied or very satisfied with accessibility by bicycle and eight out of ten with accessibility by bus and tram.

Satisfaction with public transport accessibility throughout residential areas grew from 76% to 83% over the same period. Public transport use in the Utrecht area grew 12% between 2014 and 2019, although due to Covid-19 lockdowns, public transport use almost halved in 2020. More than 800 new P+R places were created within the timescale of the plans, offering access to the city centre by sustainable modes. The share of residents in the Utrecht municipality travelling by car to the city centre dropped by 1-2%. In addition, the mobility management programme that targeted employers and commuters resulted in more than 17,000 avoided trips per day since 2019. Furthermore, charging points and electric vehicle use has increased significantly. Utrecht received attention for its development of innovative Smart Solar Charging, a bidirectional charging system for electric cars. The project was a finalist in the 2020 Regiostars Awards and won the 2021 Fully Charged CITIES award. As a result of the many changes to create more and better space for walking and cycling, and the introduction of 30km/h speed limits, traffic safety has also increased; accidents and casualties fell between 2015-2021 by almost 40% and 60%, respectively.

Challenges, opportunities and transferability

Utrecht has shown that it is possible to achieve a high modal share of sustainable modes of transport. Key to the success has been the development of a high-quality cycling and pedestrian network, making improvements at the neighbourhood level around points of interest as well as developing a city-wide network of appropriate routes. The city made some bold choices to create space and facilities for sustainable modes, including public transport, and is continuing to do so. New urban developments focus on densification around (public) transport hubs. One such development is the Merwede canal district – a brownfield site which is being redeveloped into a mixed-use area with housing for 12,000 new residents, but with virtually no space for cars. Elsewhere in the city, Utrecht aims to reduce the number of parking spaces by some 750 to 1,500 (0.5-1%) per year.

In order to keep up with the expected growth of the city, Utrecht adopted an updated SUMP in 2021, the Mobility Plan 2040. The basics from the 2016 mobility plan remain. However, the new plan adds some important elements, including a shift in focus and more decisive action in favour of certain solutions. The main ones are:

- Network for public transport: The new mobility plan further develops the ‘Wheel with Spokes’ (i.e. a network that connects different routes to hubs) concept as the backbone of the public transport network, including by specifying ‘spoke’ and ‘wheel’ connections and public transport nodes.

- Network for the bicycle: This now focuses to a greater extent on spreading bicycle traffic over the main cycle routes, and on making these safe and attractive for the large flows of cyclists, with connections to public transport, including through tangential routes circumventing the city centre.

- Network for multimodal journeys: This focuses on the creation of a network of attractive P+R locations in the region, where drivers can easily transfer to public transport, (shared) bicycle and other forms of shared transport.

- Travel differently: Encouraging “working from home” and travelling outside of rush hours. This includes taking advantage of the opportunities that now arise from the new insights about the potential of “remote working” learned during the Covid-19 period.

- Smart parking: Facilitating initiatives by residents for the redevelopment of residential streets, in which parking spaces are transformed into spaces for playing, parking bicycles and greenery. Parking is happening less and less at these destinations and more outside of these neighbourhoods. Visitors can now easily park at a 'P+R' location outside of the ring road.

- Smart planning: In the areas where space for transport is scarce and the quality of the space is of the utmost importance, Utrecht prioritises the accommodation of sustainable modes. Pedestrians and cyclists are given priority here and through-traffic by car is banned.

In Depth

- Mobility Plan 2040

- Utrecht Monitor

- Sustainable mobility rankings at national level (in Dutch)

Related items on Eltis:

- https://www.eltis.org/in-brief/news/utrecht-named-most-bike-friendly-city-2022

- https://www.eltis.org/in-brief/news/utrecht-wins-2021-fully-charged-cities-award

- https://www.eltis.org/in-brief/news/new-mobility-services-drive-healthier-cities

- https://www.eltis.org/in-brief/news/most-effective-ways-reduce-number-cars-city-centres

Author: Michael Modijefsky

Views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not reflect those of the European Commission.

Photo Credits: © Olena Znak / Shutterstock.com - no permission to re-use image(s) without separate licence from Shutterstock.