- Topic

- Mobility management

- Country

- Europe-wide

- Resource type

- Case study

First published on 28 November 2022.

Urban roads and streets in Europe are under growing pressure as they seek to accommodate increased levels and new forms of mobility, as well as dealing with a greater reliance on 'just in time' deliveries and services.

At the same time, reduced car use and the encouragement of more sustainable and active mobility are urgently needed. Indeed, many cities have pledged to be climate neutral by 2030, and while “low hanging fruit”, such as electric charging infrastructure, are undoubtedly needed, they will not be enough.

To address these challenges, governments are increasingly focussing on developing attractive spaces to support active travel and street activities. However, in busy areas, road space is unable to fully meet all of the demands put upon it, which means that road space allocation becomes a contentious issue.

Decisions to redesign roads are often made on an ad-hoc political basis, without a rigorous and comprehensive street-design process in place, and there are no methods to assist in the generation of street design options or enable the assessment of the desirability of different options.

The EU-funded MORE project (Multi-modal optimisation for road-space in Europe) has developed a comprehensive process for the allocation of road space. It considers the impact on all road users, while also taking into account cities’ economic, social, and environmental objectives.

Context

Cars and the associated infrastructure, such as roads and parking spaces, take up a significant amount of urban public space – some estimates put this at nearly 80% of city space – and in a way which has a detrimental impact on the most vulnerable members of society.

Indeed, according to research from Transport Scotland, only 40 per cent of households with an income of up to £10,000 in Scotland have access to a car; while this figure is 97 per cent for incomes over £40,000.

At the same time, air pollution is the number one killer of children in Europe and the US, as well as being one of the main drivers of long-term health problems.

In pursuit of climate neutrality targets, cities and regions across Europe are reallocating space at a growing speed. From Brussels’ Good Move to London’s ULEZ expansion, there have been a variety of ways cities prioritise more sustainable transport modes while gradually restricting space for cars.

However, reducing the space available to the car is not a straightforward process: it requires a careful and considered dialogue with a range of stakeholders, as well as the testing (and re-testing) of solutions on the ground.

The MORE project has developed tools and identified the changes needed for the governance of streets and street design, as well as identified examples of best practice from the cities involved in the project.

In action

The MORE consortium comprised a multidisciplinary team of 18 European partners: five cities (Budapest, London, Lisbon, Malmo and Constanta), three universities, five private sector companies, and five organisations representing cities and specific street-user groups.

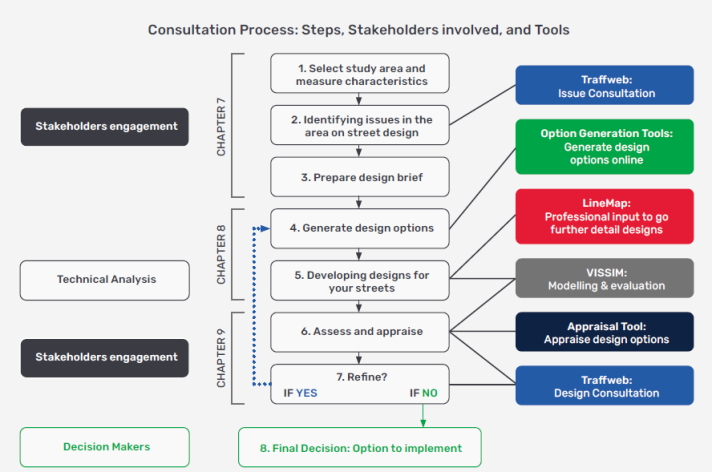

The project sought to identify and synthesise ‘good practice’ in urban road planning, design, operation, and management, while developing a set of comprehensive appraisal tools for assessing street-space design options, using the outputs from a simulation tool. The aim was to make it easier for transport leaders and technical colleagues to make the tough decisions needed.

Several different tools were developed:

- Option generation tool: a library with design elements to support the development of new options;

- A stakeholder engagement tool: for the co-creation of design options, using both web-based (LineMap and Traffweb) and traditional planning tools;

- A simulation tool: which mimics user behaviour in streets and on roads, and includes the generation of performance indicators;

- An appraisal tool: for the assessment of the design options.

Change starts at the top

In addition to the practical web-based tools, the project explored how governance approaches should also be adapted to meet the required change in urban design. This covered the following elements:

- Leadership and policy narrative: designate champions to support ‘policy entrepreneurs’ and newly formed departments.

- Administrative structures and capacity building: accumulate policy resources, compete for national and EU funds and create partnerships with the private sector.

- Design standards and indicators: using national guidance on urban street design, yet remembering the importance of context-specific design, i.e. there is no “one design fits all solution”. Guidance and performance indicators also need to be further developed.

- Dialogue with residents and stakeholder groups: create formalised space for dialogue between a variety of stakeholders (public, technical experts, elected officials, etc.).

- Standard setting and international networking: engagement should be enhanced with international working groups on standards and norms for cyber security, artificial intelligence, digitisation of streets and surveillance technologies.

Results

Streets as ecosystems

The MORE project placed an emphasis on the changing role of streets, which can vary by day, week and season. Thus, the tool highlights how space allocation may need to be altered temporarily to accommodate these varying demands in order to get the best out of the limited street space available. Therefore, in current and future street ecosystems, optimising and adapting street design will be essential to accommodate the varying patterns of demand.

Strategies such as using kerbside parking spaces for restaurant dining (tables and chairs) at night, or allowing unrestricted parking in loading bays during the evening, are just some examples of adapting the way in which space is used according to different patterns of user needs at different times.

COVID-19 and its effects on urban mobility has revealed the urgency for such flexibility, yet also the capacity of our cities to implement changes at rapid – and previously unseen – speeds.

The Hague and Rotterdam are examples of the required flexibility. The Hague experimented with a plastic platform with built-in cycle racks inserted into car parking spaces. Over the subsequent two months, residents had a chance to give feedback. The verdict was that 86 per cent of people living on the street approved of the change. As a result, the city installed a permanent cycle rack and moved the temporary platform (in Dutch, a fietsvlonder, or bicycle platform) to another neighbourhood to repeat the experiment there.

Rotterdam now has more than 70 temporary sets of cycle parking facilities circulating throughout the city, and nearly 90 parking spots have been converted into permanent parking for hundreds of bikes.

MORE pilot in Lisbon

Examining the work of Lisbon highlights the importance of flexible thinking and action, as facilitated by the MORE project, particularly in cases where cities are faced with short- and long-term uncertainties around urban mobility. The city has been developing comprehensive active travel plans, yet implementation of these on the ground has proved complex.

In the Portuguese capital, four scenarios were developed, which varied by demographic, employment and technology factors. This allowed them to be applied to different zones of the city. Each of these scenarios have different implications for the type of action that might be needed to promote active travel. The scenarios developed were:

Scenario 1: based on tourism growth, which will help to redefine existing commerce and services in the zone and its impacts on demography and economy.

Scenario 2: relies on the success of some housing policies and the emergence of some clusters of technology start-up companies in the zone’s area of influence, which attract a younger generation to live in the zone.

Scenario 3: assumes a similar composition that has happened in surrounding neighbourhoods, with a significant immigrant population moving to the zone, which changes the type of commerce and rejuvenating the area.

Scenario 4: considers the hypothesis of large restrictions to internal combustion engine vehicles circulating in the city centre and its surroundings and the progressive transformation that can occur in the economy and demography in this area.

Using these scenarios helped the city to identify several possible adaptations to bus lanes, parking provision and pavements, while identifying possible negative effects.

Challenges, opportunities and transferability

The MORE project has encouraged practitioners to view the street from different perspectives and as a holistic ecosystem, which involved bringing together a much wider range of professionals than would normally be involved in street design. This has helped to foster cross departmental cooperation.

The process has had key learning for other practitioners seeking to redesign urban streets to accommodate a range of user needs whilst putting cities on track to achieve their climate neutrality targets.

The stakeholder engagement process can – and is being – replicated by many cities. The project underlined the importance of extensive stakeholder engagement, from defining the problem and generating options, right through to the appraisal of options and making decisions, which is a substantial change from the usual passive consultation.

Indeed, the importance of taking such an approach was the finding of a recent report “Fairly reducing car use in Scottish cities: A just transition for transport for low-income households”, which sought to understand the opportunities for car reduction and align the policy responses to the climate and nature crises with the need to tackle existing social inequality and improve people’s quality of life. It also highlighted the uncertainty of many low-income communities about car reduction policies and pricing mechanisms.

This can be seen in London where it has been essential to ensure that all voices were heard during the consultation for the city’s Ultra-Low Emissions Zone (ULEZ), which is due to take effect in August 2023. While there will be exemptions and discounts for vehicles registered for carrying disabled passengers and wheelchair-accessible private hire vehicles, the potential impact on such groups needs to be fully understood and accounted for.

Meanwhile, Leuven's citizen participation model around their circulation plan also inspires the broad partnership required to achieve this. This has been done through Leuven 2030, a non-profit organisation which convenes 600 local partners and civil society representatives, all working towards the goal of climate neutrality through small and large-scale actions and projects. An active advisory group also supports the organisation in catering for the needs of disabled users and advises on different mobility rights and supporting measures needed for disabled people.

To conclude, the MORE project’s tools will help practitioners to design open dialogues with stakeholders and adapt the process to their local context, while reaching a consensus on the design of streets that have competing demands for their limited space.

Author: Isobel Duxfield

Views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not reflect those of the European Commission.

Image Credits: MORE Project